Nobody Works for Free.

Why do you go to work every day? Why do you spend hours baking delicious homemade chocolate chip cookies? Why do you give your child the iPad when they’re screaming? Why do you keep ordering things you don’t need from Amazon? Behold… the power of REINFORCEMENT! For better or worse, reinforcement increases the likelihood that a behavior will happen again under similar conditions. In short, reinforcement is the motivation behind our behavior. Reinforcement comes in many forms, for instance, one may find a tangible object or activity reinforcing (mmm… chocolate!) or one may find escape from an aversive stimulus reinforcing (oops… my “quick trip” ALONE to Target turned into a 3 hour stroll down every aisle). Let’s explore the Do’s and Don’t’s of using reinforcement with children effectively.

DO:

Consider value

It’s important to establish a reinforcement hierarchy. I can tell you that I’d much rather work for an hour of uninterrupted Netflix binge-watching than a bowl full of cookie dough ice cream. Will I work for both? Yes, but you’ll probably see me work more efficiently if I know that there’s a new episode of This Is Us waiting for me. Offer your child something more highly reinforcing for a more difficult task.

Keep in mind that something cannot be defined as a reinforcer if it doesn’t increase the likelihood of recurring behavior. You can throw Skittles at me all day long. I’ll eat them and I’ll enjoy them, but it doesn't mean that I’ll work for them. We can’t necessarily expect that kids will work for what we want them to work for, it must be reinforcing to them.

Consider Immediacy

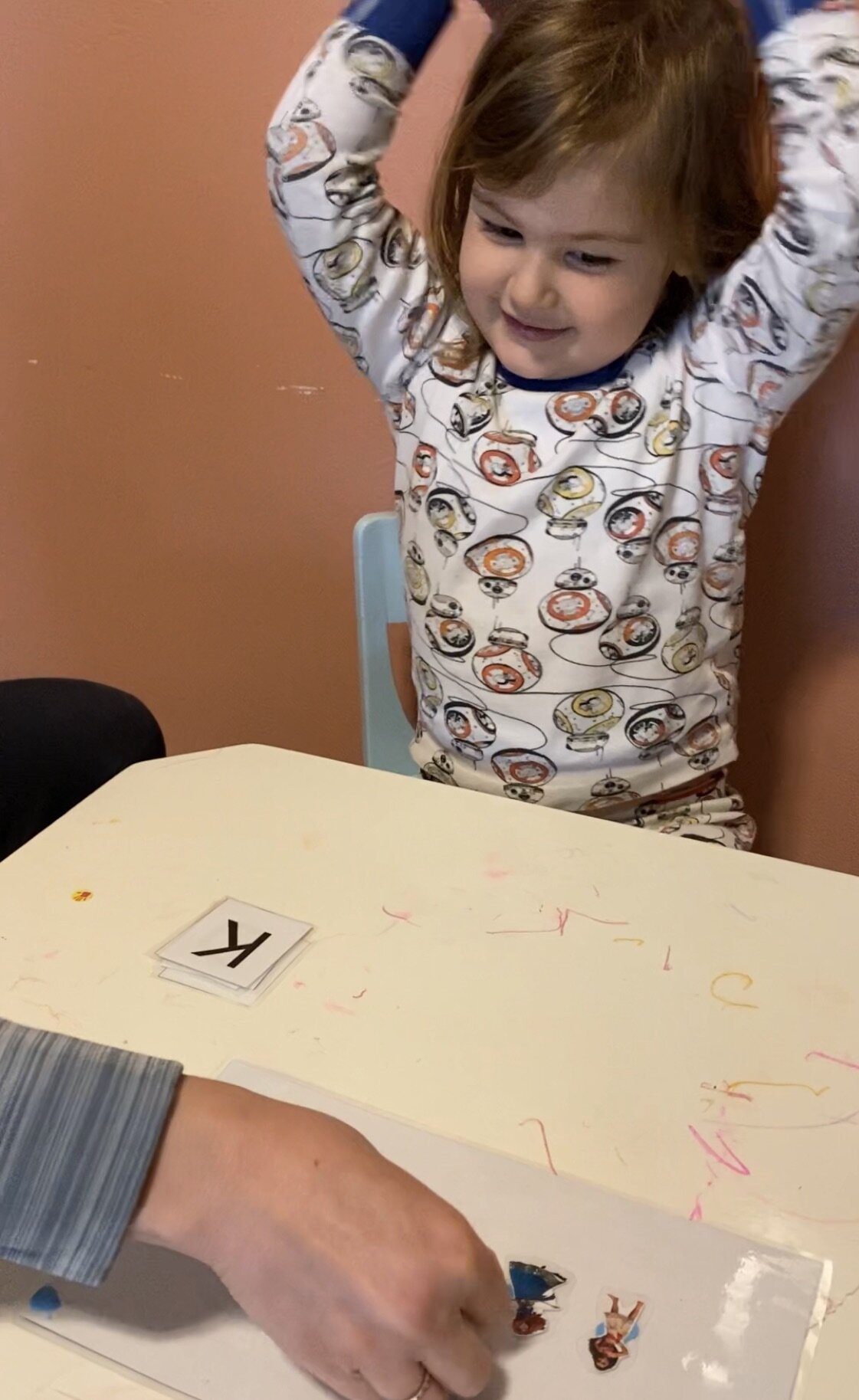

It can be difficult enough for adults to wait for delayed reinforcement let alone a child. You’ll establish a new skill much quicker if you give your child immediate feedback: “Did you just get your jammies on the first time I asked?! Whoa, amazing! Let’s go watch 15 minutes of your favorite TV show before story time” is going to be more impactful than, “Did you just get your jammies on the first time I asked?! Whoa, amazing! Let’s go read a book and you can watch your favorite show in the morning.” Chances are, your child will have forgotten about the show in the morning, whereas if they’ve accessed their favorite TV show in that moment, they’ll more likely make that connection the next time they are told to put on their jammies.

Consider magnitude

I’ll never forget potty training my oldest. Dang, that girl had it all figured out. We sat in the bathroom for hours with very little success over the course of 3 days, but on day 4 I was desperate. I upped the ante and offered her the ENTIRE PACK of fruit snacks for ONE PEE. And just like that, within the next 12 hours and an enormous amount of fruit snacks later, she was potty trained (worth it).

I’ll sound like a broken record here, but something is not a reinforcer unless it is effective in increasing the likelihood of a behavior occurring again. The thing is, I was certain that fruit snacks were her favorite treat, so what was the problem? Well, when you think about your own work-reward contingencies, you’ve also set your price. You’ll work for money, sure, but it needs to be worth your time. You’re not going to spend 8 hours in the office for $10; your hard work is worth a fair wage. Why would it be any different for our kids?

DON’T:

Delay reinforcement

The rule of thumb is that, when you deliver a reinforcer, you are reinforcing the behavior that immediately preceded the delivery of the reinforcer. Be very careful not to inadvertently reinforce undesirable behavior. Let’s say, for instance, that you tell your child that they can have a sucker if they listen and follow directions at the grocery store. Your child is a rockstar; they stay by your side, they keep calm and quiet through the checkout line. However, on the way home they begin whining, because they want to go to the park. You pull in the driveway, and tell them to go pick out their sucker. You are now reinforcing (increasing the future likelihood) of whining. In this example, it would be wise to bring a sucker to the store and give it to your child as soon as they get buckled in the car for the ride home.

Fall into the trap of mutual reinforcement

If there’s a parent out there that says they’ve never given into their crying child by giving them what they wanted - they’re lying. At some point, every parent has given into a tantrum. When the parent gives into the child’s demands, the child stops crying. This removal of crying has now reinforced the parent’s giving in, which means that the parent is more likely to give in next time-to stop the crying AND the child is more likely to cry next time. This vicious cycle is called mutual reinforcement, and it’s a slippery slope when it comes to managing behavior effectively. Pro tip: If you need a minute to get something done, try plopping your child in front of the TV before you begin instead of waiting for them to have a melt down (it’s ok, we all do it), but if your child ends up having a meltdown anyway, you now have the option to turn off the TV (which should then discourage meltdowns in the future).

It may become obvious that the DO’s of reinforcement focus on strategies that reinforce desirable behavior, whereas the DON’T’s of reinforcement focus on the caution against reinforcing undesirable behavior. If you are careful only to provide your child with reinforcement when they are engaging in appropriate behavior, you set clear expectations that only “good” behavior is worth their time and energy.